Overview

This blog is about SSL or TLS communication, it explains in depth about the Protocols used, Handshake mechanism. Also the respective responsibilities of TCP and TLS protocols in a Secure, Reliable communication.

History:

- First SSL prototypes came from Netscape when they were developing the first versions of their flagship browser, Netscape Navigator.

- SSL version 3 (SSLv3) was an enhanced protocol which still works today and is widely supported. The protocol has been standardized, with a new name in order to avoid legal issues; the new name is TLS.

- Four versions of TLS have been produced so far, each with its dedicated RFC: TLS 1.0, TLS 1.1, TLS 1.2 and TLS 1.3.

- TLS 1.0 and 1.1 are now deprecated in 2020.

- TLS 1.2 removed the backward compatibility with SSL such that TLS sessions never negotiate the use of Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) version 2.0.

- TLS 1.2 Improvements

- AWS IoT still supports TLS 1.2 only.

- TLS 1.3 is fully supported by Firefox, Chrome, wolfSSL.

- TLS 1.3 Improvements

- Mandating perfect forward secrecy, by means of using ephemeral keys during the (EC)DH key agreement

- Prohibiting SSL or RC4 negotiation for backwards compatibility

- Encrypting all handshake messages after the ServerHello

- TLS 1.3 Improvements

TCP and TLS

- TCP assumes the responsibility of Reliable data communication.

- SSL/TLS aims at providing a Secure bidirectional tunnel for arbitrary data.

TCP in brief:

- TCP is the well-known protocol for sending data over the Internet.

- TCP works over the IP “packets” and provides a bidirectional tunnel for bytes; it works for every byte values and sends them into two streams which can operate simultaneously.

- TCP handles the hard work of splitting the data into packets, acknowledging them, reassembling them back into their right order, while removing duplicates and reemitting lost packets.

- From the point of view of the application which uses TCP, there are just two streams, and the packets are invisible; in particular, the streams are not split into “messages” (it is up to the application to take its own encoding rules if it wishes to have messages, and that’s precisely what HTTP does).

Why SSL/TLS:

- TCP is reliable in the presence of “accidents”, i.e. transmission errors due to flaky hardware, network congestion, people with smartphones who walk out the range of a given base station, and other non-malicious events.

- However, an ill-intentioned individual (the “attacker”) with some access to the transport medium could read all the transmitted data and/or alter it intentionally, and TCP does not protect against that.

- Hence SSL.

- SSL assumes that it works over a TCP-like protocol, which provides a reliable stream;

- SSL does not implement reemission of lost packets and things like that. The attacker is supposed to be in power to disrupt communication completely in an unavoidable way (for instance, he can cut the cables)

- so SSL’s job is to:

- detect alterations (the attacker must not be able to alter the data silently);

- ensure data confidentiality (the attacker must not gain knowledge of the exchanged data).

- SSL fulfills these goals to a large (but not absolute) extent.

Record Protocol:

- SSL is layered and the bottom layer is the record protocol.

- Whatever data is sent in an SSL tunnel is split into records.

- Over the wire (the underlying TCP socket or TCP-like medium), a record looks like this:

HH V1:V2 L1:L2 data- HH is a single byte which indicates the type of data in the record.

- Four types are defined:

- change_cipher_spec (20)

- alert (21)

- handshake (22)

- application_data (23)

- Four types are defined:

- V1: V2 is the protocol version, over two bytes.

For all versions currently defined,

- V1 has value 0x03, while V2 has value 0x00 for SSLv3,

- 0x01 for TLS 1.0

- 0x02 for TLS 1.1

- 0x03 for TLS 1.2

- L1: L2 is the length of data, in bytes (big-endian convention is used: the length is 256*L1+L2).

- The total length of data cannot exceed 18432 bytes, but in practice, it cannot even reach that value.

- HH is a single byte which indicates the type of data in the record.

- So a record has a five-byte header, followed by at most 18 kB of data.

- The data is where symmetric encryption and integrity checks are applied.

- When a record is emitted, both sender and receiver are supposed to agree on which cryptographic algorithms are currently applied, and with which keys; this agreement is obtained through the handshake protocol. Compression, if any, is also applied at that point.

Record protocol works like this:

- Initially, there are some bytes to transfer; these are application data or some other kind of bytes. This payload consists of at most 16384 bytes, but possibly less (a payload of length 0 is legal, but it turns out that Internet Explorer 6.0 does not like that at all).

- The payload is then compressed with whatever compression algorithm is currently agreed upon.

- Compression is *stateful* and thus may depend upon the contents of previous records.

- In practice, compression is either “null” (no compression at all) or “Deflate” (RFC 3749),

- the latter being currently courteously but firmly shown the exit door in the Web context, due to the recent CRIME attack.

- Compression aims at shortening data, but it must necessarily expand it slightly in some unfavorable situations (due to the pigeonhole principle).

- SSL allows for an expansion of at most 1024 bytes. Of course, null compression never expands (but never shortens either); Deflate will expand by at most 10 bytes if the implementation is any good.

- The compressed payload is then protected against alterations and encrypted.

- If the current encryption-and-integrity algorithms are “null”, then this step is a no-operation.

- Otherwise, a MAC is appended, then some padding (depending on the encryption algorithm), and the result is encrypted.

-

These steps again induce some expansion, which the SSL standard limits to 1024 extra bytes (combined with the maximum expansion from the compression step, this brings us to the 18432 bytes, to which we must add the 5-byte header).

- The MAC is, usually, HMAC with one of the usual hash functions (mostly MD5, SHA-1 or SHA-256)(with SSLv3, this is not the “true” HMAC but something very similar and, to the best of our knowledge, as secure as HMAC).

- Encryption will use either a block cipher in CBC mode, or the RC4 stream cipher.

- Crucially, the MAC is first computed and appended to the data, and the result is encrypted.

- This is MAC-then-encrypt and it is actually not a very good idea. The MAC is computed over the concatenation of the (compressed) payload and a sequence number, so that an industrious attacker may not swap records.

Handshake:

- The handshake is a protocol which is played within the record protocol with content type = 22.

- Its goal is to establish the algorithms and keys which are to be used for the records.

- It consists of messages. Each handshake message begins with a four-byte header,

- one byte which describes the message type,

- then three bytes for the message length (big-endian convention).

-

The successive handshake messages are then sent with records tagged with the “handshake” type (the first byte of the header of each record has value 22(~content type)).

- Initially, client and server “agree upon” null encryption with no MAC and null compression. This means that the record they will first send will be sent as cleartext and unprotected.

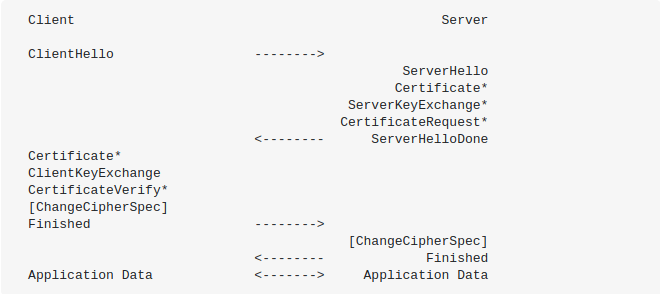

Full Handshake (Mutual Authentication)

-

The full handshake looks like this:

- ClientHello:

- The first message of a handshake is a ClientHello.

- It is the message by which the client states its intention to do some SSL. (Note that “client” is a symbolic role; it means “the party which speaks first”.)

- The ClientHello message contains:

- the Highest protocol version that the client wishes to support;

- the client random (32 bytes, out of which 28 are supposed to be generated with a cryptographically strong number generator);

- the session ID (in case the client wants to resume a session in an abbreviated handshake, see below);

- the list of cipher suites that the client knows of, ordered by client preference;

- the list of compression algorithms that the client knows of, ordered by client preference;

- some optional extensions.

- The first message of a handshake is a ClientHello.

- ServerHello:

- The server responds to the ClientHello with a ServerHello which contains:

- the protocol version that the client and server will use;

- the server random (32 bytes, with 28 random bytes);

- the session ID for this connection;

- the cipher suite that will be used;

- the compression algorithm that will be used;

- optionally, some extensions.

- The server responds to the ClientHello with a ServerHello which contains:

- Besides ClientHello and ServerHello, the server sends a few other messages, which depend on the cipher suite and some other parameters:

- Certificate: the server’s certificate, which contains its public key. This message is almost always sent, except if the cipher suite mandates a handshake without a certificate.

- ServerKeyExchange: some extra values for the key exchange, if what is in the certificate is not sufficient. In particular, the DHE cipher suites like DHE & ECDHE use an ephemeral Diffie-Hellman key exchange, which requires that message.

- CertificateRequest: a message to request the client to also identify itself with a certificate of its own. This message contains the list of names of trust anchors (aka “root certificates”) that the server will use to validate the client certificate.

- ServerHelloDone: a marker message (of length zero) which says that the server is finished, and the client should now talk.

- The client must then respond with:

- Certificate: the client certificate, if the server requested one. There are subtle variations between versions (with SSLv3, the client must omit this message if it does not have a certificate; with TLS 1.0+, in the same situation, it must send a Certificate message with an empty list of certificates).

- ClientKeyExchange: the client part of the actual key exchange (e.g. some random value (~PreMasterSecrete) encrypted with the server RSA public key).

- The client and server then use the random numbers and PreMasterSecret to compute a common secret, called the master secret. All other key data (session keys such as IV, symmetric encryption key, MAC key) for this connection is derived from this master secret (and the client- and server-generated random values), which is passed through a carefully designed pseudorandom function.

- CertificateVerify: a digital signature computed by the client over all previous handshake messages. This message is sent when the server requested a client certificate, and the client complied. This is how the client proves to the server that it really "owns" the public key which is encoded in the certificate it sent.

- Initial Handshake is over by now.

- With following messages Client and Server will switch over to encrypted communication.

- ChangeCipherSpec: Then the client sends a ChangeCipherSpec message, which is not a handshake message: it has its own record type with content type = 20, so it will be sent in a record of its own. Its contents are purely symbolic (a single byte of value 1). This message marks the point at which the client switches to the newly negotiated cipher suite and keys. The subsequent records from the client will then be encrypted.

- Finished: The Finished message is a cryptographic checksum computed over all previous handshake messages (from both the client and server). Since it is emitted after the ChangeCipherSpec, it is also covered by the integrity check (containing a hash and MAC over the previous handshake messages) and the encryption.

- When the server receives Finished message and verifies its contents, it obtains a proof that it has indeed talked to the same client all along. This message protects the handshake from alterations (the attacker cannot modify the handshake messages and still get the Finished message right).

- The server finally responds with its own ChangeCipherSpec then Finished.

- Client performs the same decryption and verification procedure as the server did in the previous step.

- At that point, the handshake is finished, and the client and server may exchange application data (in encrypted records tagged as such). The application protocol is enabled, with content type = 23.

- Application messages exchanged between client and server will also be authenticated and optionally encrypted exactly like in their Finished message. Otherwise, the content type will = 25 and the client will not authenticate.

Basic Handshake

- In this handshake, only Server is Authenticated with it’s Server Certificate.

- Client Certificate is not mandatory.

- Flow of Handshake will same as Full Handshake, but without few messages getting excanged as:

- CertificateRequest message will not be sent by Server in this case.

- Client will not send the Certificate message with it’s own certificate.

- Client will not send the CertificateVerify message.

- Otherwise, all messages of Full Handshake will be exchanged.

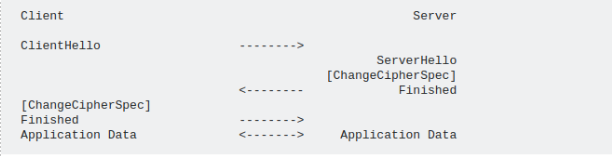

Abbreviated/Resumed Handshake:

- In the full handshake, the server sends a “session ID” (i.e. a bunch of up to 32 bytes) to the client.

- Later on, the client can come back and send the same session ID as part of his ClientHello. This means that the client still remembers the cipher suite and keys from the previous handshake and would like to reuse these parameters.

- If the server also remembers the cipher suite and keys, then it copies that specific session ID in its ServerHello, and then follows the abbreviated handshake:

- The abbreviated handshake is shorter: fewer messages, no asymmetric cryptography business, and, most importantly, reduced latency.

- A typical Web browser will open an SSL connection with a full handshake, then do abbreviated handshakes for all other connections to the same server: the other connections it opens in parallel, and also the subsequent connections to the same server.

- Indeed, typical Web servers will close connections after 15 seconds of inactivity, but they will remember sessions (the cipher suite and keys) for a lot longer (possibly for hours or even days).

- Resumed sessions can also be used for single sign-on, as it guarantees that both the original session and any resumed session originate from the same client.

- Resumed Sessions are of particular importance for the FTP over TLS/SSL protocol, which would otherwise suffer from a man-in-the-middle attack in which an attacker could intercept the contents of the secondary data connections.

Handshake Re-initiation:

- At any time, the client or the server can initiate a new handshake (the server can send a HelloRequest message to trigger it; the client just sends a ClientHello).

- A typical situation is the following:

- An HTTPS server is configured to listen to SSL requests.

- A client connects and a handshake is performed.

- Once the handshake is done, the client sends its “applicative data”, which consists of an HTTP request. At that point (and at that point only), the server learns the target path. Up to that point, the URL which the client wishes to reach was unknown to the server (the server might have been made aware of the target server name through a Server Name Indication SSL extension, but this does not include the path).

- Upon seeing the path, the server may learn that this is for a part of its data which is supposed to be accessed only by clients authenticated with certificates. But the server did not ask for a client certificate in the handshake (in particular because not-so-old Web browsers displayed freakish popups when asked for a certificate, in particular, if they did not have one, so a server would refrain from asking a certificate if it did not have good reason to believe that the client has one and knows how to use it).

- Therefore, the server triggers a new handshake, this time requesting a certificate.

Session Tickets

- RFC 5077 extends TLS via use of Session Tickets, instead of Session IDs.

- It defines a way to resume a TLS session without requiring that session-specific state is stored at the TLS server.

- Instead the TLS server stores its session-specific state in a session ticket and sends the session ticket to the TLS client for storing.

- The client resumes a TLS session by sending the session ticket to the server, and the server resumes the TLS session according to the session-specific state in the ticket.

- The session ticket is encrypted and authenticated by the server, and the server verifies its validity before using its contents.

- OpenSSL weakness in this method:

- OpenSSL always limits encryption and authentication security of the transmitted TLS session ticket to

AES128-CBC-SHA256, no matter what other TLS parameters were negotiated for the actual TLS session. - This means that the state information (the TLS session ticket) is not as well protected as the TLS session itself.

- Of particular concern is OpenSSL's storage of the keys in an application-wide context (SSL_CTX), i.e. for the life of the application, and not allowing for re-keying of the "AES128-CBC-SHA256" TLS session tickets without resetting the application-wide OpenSSL context (which is uncommon, error-prone and often requires manual administrative intervention).

- OpenSSL always limits encryption and authentication security of the transmitted TLS session ticket to

TLS Content Types:

| Hex | Dec | Type |

|---|---|---|

| 0x14 | 20 | ChangeCipherSpec |

| 0x15 | 21 | Alert |

| 0x16 | 22 | HandShake |

| 0x17 | 23 | Application |

| 0x18 | 24 | Heartbeat |

Cipher Suite:

- A cipher suite is a 16-bit symbolic identifier for a set of cryptographic algorithms.

- For instance, the TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA cipher suite has value 0x002F,

- and means records use HMAC/SHA-1 and AES encryption with a 128-bit key,

- and the key exchange is done by encrypting a random key with the server’s RSA public key”.

- the client suggests but the server chooses.

- The cipher suite is in the hands of the server. Courteous servers are supposed to follow the preferences of the client (if possible), but they can do otherwise and some actually do (e.g. as part of protection against BEAST).

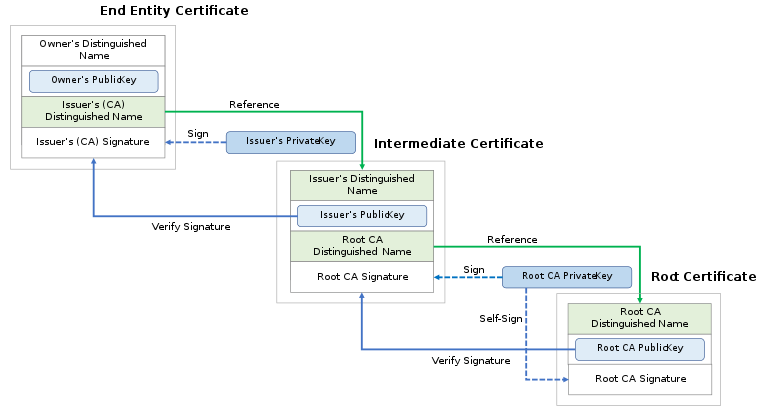

Certificates

- The certificate is a vessel for the Server Public Key, Identity of its Owner, digital signature of an entity that has verified the certificate’s contents (issuer, CA).

- It is used to thwart active attackers who would want to impersonate the server: such an attacker intercepts the communication and sends its RSA Public Key instead of the server’s.

- The certificate is signed by a certification authority, so that the client may know that a given RSA Public Key is really the genuine one from the server he wants to talk with.

- Digital signatures also use asymmetric cryptography, although in a distinct way (for instance, there is also a variant of RSA for digital signatures).

- X.509 is the most common format for public key certificates.

Chain of Trust

Most Common Fields in certificates

- Serial Number: Used to uniquely identify the certificate within a CA’s systems. In particular this is used to track revocation information.

- Subject: The entity a certificate belongs to: a machine, an individual, or an organization.

- Issuer: The entity that verified the information and signed the certificate.

- Not Before: The earliest time and date on which the certificate is valid. Usually set to a few hours or days prior to the moment the certificate was issued, to avoid clock skew problems.

- Not After: The time and date past which the certificate is no longer valid.

- Key Usage: The valid cryptographic uses of the certificate’s public key. Common values include digital signature validation, key encipherment, and certificate signing.

- Extended Key Usage: The applications in which the certificate may be used. Common values include TLS server authentication, email protection, and code signing.

- Public Key: A public key belonging to the certificate subject.

- Signature Algorithm: This contain a hashing algorithm and an encryption algorithm. For example “sha256RSA” where sha256 is the hashing algorithm and RSA is the encryption algorithm.

- Signature: The body of the certificate is hashed (hashing algorithm in “Signature Algorithm” field is used) and then the hash is encrypted (encryption algorithm in the “Signature Algorithm” field is used) with the issuer’s private key.

TLS/SSL server certificates

- Certificates are used to trust the Servers in a Secure TLS communication as the certificate is signed by a trusted certificate authority.

- The subject of the certificate matches the hostname (i.e. domain name) to which the client is trying to connect;

- Domain name of the website is listed as the Common Name in the Subject field of the certificate.

- A certificate may be valid for multiple hostnames (multiple websites). Such certificates are commonly called Subject Alternative Name (SAN) certificates or Unified Communications Certificates (UCC). These certificates contain the field Subject Alternative Name.

- If some of the hostnames contain an asterisk (*), a certificate may also be called a wildcard certificate.

- TLS Certificates are classified as:

- Domain Validation SSL (DV)

- A certificate provider will issue a domain-validated (DV) certificate to a purchaser if the purchaser can demonstrate one vetting criterion: the right to administratively manage the affected DNS domain(s).

- Organization Validation SSL (OV)

- A certificate provider will issue an organization validation (OV) class certificate to a purchaser if the purchaser can meet two criteria:

- the right to administratively manage the domain name in question, and perhaps,

- the organization’s actual existence as a legal entity.

- A certificate provider publishes its OV vetting criteria through its certificate policy.

- A certificate provider will issue an organization validation (OV) class certificate to a purchaser if the purchaser can meet two criteria:

- Extended Validation SSL

- To acquire an Extended Validation (EV) certificate, the purchaser must persuade the certificate provider of its legal identity, including manual verification checks by a human.

- As with OV certificates, a certificate provider publishes its EV vetting criteria through its certificate policy.

- Domain Validation SSL (DV)

TLS/SSL client certificates

- These are less common and are mainly used as IoT device identity, also common in RPC systems.

- These are not usually issued by CAs but the operator of a service that requires client certificates will usually operate their own internal CA to issue them.

Code signing certificate

- Certificates can also be used to validate signatures on programs to ensure they were not tampered with during delivery.

- ToDo

Self-signed certificate

- Also referred in Cryptography as Snake Oil certificates, due to their untrustworthiness.

- ToDo